|

|

|

| |

||

| |

|

|

| |

||

|

|

||

| |

||

Early Mongolian contacts with Buddhism are dated to the fourth century, when the activities of Chinese monks among the population of this border area are reported in contemporary Chinese sources. Buddhist influences spread as far as the Yenisei region by the seventh century, as evidenced by Buddhist temple bells with Chinese inscriptions found there. Another factor in the spread of Buddhism into Mongolia was the flourishing of Buddhist communities in the predominantly Uighur oasis states along the Silk Route. Furthermore, the palace that was built by Ogedei Khan (1229-1241) in Karakorum, the Mongol capital, was constructed on the foundations of a former Buddhist temple; some of the murals from this temple have been preserved, Sources for this early Buddhist activity are rather scarce. Reports in Mongolian sources on the early spread of Buddhism shroud these missionary activities in a cloak of mysterious events that testify to the superiority of Tantric Buddhism over other religions during the reign of Khublai Khan (1260-1294). Contacts with the Sa-skya pandita Kun-dga'rgyal-mtshan (1182-1251) were established during Ogedei's reign, but Buddhism only gained influence with the Mongols after their expeditions into Tibet, which resulted in the sojourn of Tibetan monks as hostages at the Mongol court. The activities there of the lama (Tib., bla ma) 'Phags pa (1235-1280) resulted in an increase in conversions to Buddhism, his invention, in 1269, of a block script led to the translation into Mongolian of great numbers of Buddhist religious literature, the translations often based on already existing Uighur translations. The legend that Chinggis Khan had previously invited the Sa-skya abbot Kun-dga'-snin-po (1092-1158) lacks proof. In spite of

the extensive translation and printing of Buddhist tracts, conversion

seems to have been limited to the nobility and the ruling families.

Judging from the Mongols' history of religious tolerance, it is

rather doubtful that Buddhism spread among the general population

on a large scale. Syncretic influences resulted in the transformation

of popular gods into Buddhist deities and the acceptance of notions

from other religions during this period.

During the Ch'ing dynasty in China, particularly during the K'ang-hsi, Yung-cheng, and Ch'ien-lung reign periods, the printing of Buddhist works in Mongolian was furthered by the Manchu emperors as well as by the Mongolian nobility. Donating money for copying scripture, cutting printing blocks, and printing Buddhist works were thought of as meritorious deeds. Works on medicine, philosophy, and history were also published and distributed. The spiritual life of Mongolia became strongly influenced by religious and semi-religious thoughts and ethics. Sponsored by the K'ang hsi emperor, a revised edition of the Mongolian Bka''-gyur was printed from 1718 to 1720; translation of the Bstan-'gyur (Tanjur) was begun under the Ch'ien-lung emperor in 1741 and was completed in 1749. Copies of the completed edition (in 108 and 223 volumes, respectively, for the Bka'-'gyur and Bstan'-'gyur) were given as imperial gifts to many monasteries throughout Mongolia. In the eighteenth

century elements of indigenous Mongolian mythology were incorporated

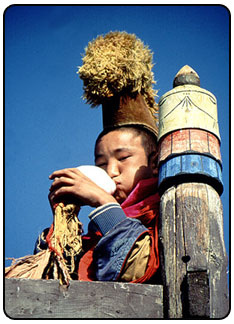

into a national liturgy Walther Heissig Photographs

by Sue Byrne (Programme Manager) |

| |

|||||||

| |

|||||||

| |

Copyright© 2008 - BDEA Inc. & BuddhaNet. All rights reserved. | |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|||||||

| |

|||||||

After

Mongol rule over China ended in 1368 the practice of Buddhism diminished

among the Mongols, deteriorating into mere superstition or giving

way once again to the indigenous religious conceptions of the Mongols

and to shamanism. It was not until the sixteenth century that a

second wave of Buddhist conversion began, brought about by the military

expeditions of Allan Khan of the Tumet (1507-1583) into the eastern

border districts of Tibet, which resulted in contacts with lamaist

clerics. Within the short period of fifty years, beginning with

the visit of the third Dalai Lama to Allan Khan's newly built residence,

Koke Khota, in 1578, practically all of the Mongolian nobility was

converted to Buddhism by the missionary work of many devoted lamaist

priests. The most famous of these were Neyici Toyin (1557-1653),

who converted the eastern Mongols, and Zaya Pandita, who converted

the western and northern Mongols. Sustained by princes and overlords

who acted according to the maxim "huius regio, eius religio,"

inducing the adoption of the new faith by donations of horses, dairy

animals, and money, the population willingly or forcedly took to

Lamaism. Shamanism was outlawed, idols sought out and burned. The

establishment of many new monasteries opened to a greater part of

the population the opportunity to become monks, resulting in a drain

on Mongolian manpower. The monasteries, however, became similar

to those of early medieval Europe; they were the cradles of literature

and science, particularly of Buddhist philosophy. By 1629 many other

lamaist works were translated into Mongolian, including the 1,161

volumes of the lamaist canon, the Bka'-'gyur (Kanjur). Tibetan became

the lingua franca of the clerics, as Latin was in medieval Europe,

with hundreds of religious works written in this language.

After

Mongol rule over China ended in 1368 the practice of Buddhism diminished

among the Mongols, deteriorating into mere superstition or giving

way once again to the indigenous religious conceptions of the Mongols

and to shamanism. It was not until the sixteenth century that a

second wave of Buddhist conversion began, brought about by the military

expeditions of Allan Khan of the Tumet (1507-1583) into the eastern

border districts of Tibet, which resulted in contacts with lamaist

clerics. Within the short period of fifty years, beginning with

the visit of the third Dalai Lama to Allan Khan's newly built residence,

Koke Khota, in 1578, practically all of the Mongolian nobility was

converted to Buddhism by the missionary work of many devoted lamaist

priests. The most famous of these were Neyici Toyin (1557-1653),

who converted the eastern Mongols, and Zaya Pandita, who converted

the western and northern Mongols. Sustained by princes and overlords

who acted according to the maxim "huius regio, eius religio,"

inducing the adoption of the new faith by donations of horses, dairy

animals, and money, the population willingly or forcedly took to

Lamaism. Shamanism was outlawed, idols sought out and burned. The

establishment of many new monasteries opened to a greater part of

the population the opportunity to become monks, resulting in a drain

on Mongolian manpower. The monasteries, however, became similar

to those of early medieval Europe; they were the cradles of literature

and science, particularly of Buddhist philosophy. By 1629 many other

lamaist works were translated into Mongolian, including the 1,161

volumes of the lamaist canon, the Bka'-'gyur (Kanjur). Tibetan became

the lingua franca of the clerics, as Latin was in medieval Europe,

with hundreds of religious works written in this language. composed

entirely in Mongolian. A century later there were about twelve hundred

lamaist temples and monasteries in Inner Mongolia and more than

seven hundred in the territory of the present-day Mongolian People's

Republic. More than a third of the entire male population of Mongolia

belonged to the clergy. The monasteries, possessing their own economic

system and property, formed a separate administrative and political

organization. In the twentieth century the decline of monasteries

and Lamaism was brought about by inner strife and a changing moral

climate as well as by political movements and new ideologies. Recently

have some monasteries been reopened in the Mongolian parts of China,

in the Mongolian People's Republic, and in Buriat-Mongolia in the

former U.S.S.R., but the question of whether the younger members

of the population will embrace the faith again remains open.

composed

entirely in Mongolian. A century later there were about twelve hundred

lamaist temples and monasteries in Inner Mongolia and more than

seven hundred in the territory of the present-day Mongolian People's

Republic. More than a third of the entire male population of Mongolia

belonged to the clergy. The monasteries, possessing their own economic

system and property, formed a separate administrative and political

organization. In the twentieth century the decline of monasteries

and Lamaism was brought about by inner strife and a changing moral

climate as well as by political movements and new ideologies. Recently

have some monasteries been reopened in the Mongolian parts of China,

in the Mongolian People's Republic, and in Buriat-Mongolia in the

former U.S.S.R., but the question of whether the younger members

of the population will embrace the faith again remains open.